Mawson's forgotten men weathered it all, only to be frozen out of history

First published in The Australian - Health and Science. 07/01/2012

Exactly 100 years ago, on January 8 1912, a brilliant ice-master brought his refitted whaling ship safely into an Antarctic bay studded with snow-capped rocks.

Captain John King Davis was not hunting leviathans, he was searching for a place to land the second party of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition. The water was Commonwealth Bay. Beside Davis on the bridge stood the expedition's leader Douglas Mawson, rather green about the gills after weeks of seasickness.

Five young men had already been set ashore on Macquarie Island. Mawson and another 17 would be set down at Cape Denison and eight men would be taken 2410km west before a coal crisis saw them landed on the Shackleton Glacier. Three separate land parties!

Why do we hear only one name and one base associated with that expedition? How many times have you read that Douglas Mawson explored and mapped a huge slice of Antarctica, that he took the scientific measure of the ice-wilderness? Ever wondered how one man could do so much?

The truth is he didn't. Thirty intrepid, educated, skilled, determined young men did at least their share of the land exploration; Captain John King Davis and his crew, helped by certain expeditioners when aboard, did the charting of more than 4000km of coastline and vast stretches of sea floor. Why are they not acknowledged? Why does no one know about them? Even during the Antarctic centenary celebrations, we are still being dished up hagiographies of one man. It is time to establish who was there and who did what.

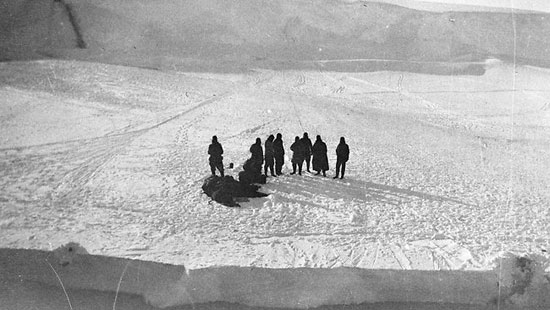

The Western Base party, photographed by Second Mate Gray from the Aurora as the ship pulled away on February 21, 1912.

Picture: Mitchell Library Source: Supplied

On Macquarie Island, George Ainsworth led the party. Seconded from the Commonwealth Meteorological Bureau, Ainsworth established the weather station whose reports still today help us decide whether to take an umbrella with us. Telegraphers Sandell and Sawyer took turns climbing Wireless Hill to listen throughout the long nights of 1912 for messages that never came from the main base, where the wireless aerial was a saga of disasters. Biologist Harold Hamilton and geologist Leslie Blake, despite the island's vile climate, spent much of their time in the field, holed up in caves, living quite well off the island's wildlife. King penguin omelettes and sea elephant tongue gave them the latitude to stay out sometimes for weeks and when resupply of the island failed in 1913 these two men kept native victuals up to the increasingly hungry station.

Hamilton catalogued the fauna and his subsequent scientific papers leapt with the excitement of new frog species. Not so the tragic Blake. There would be no papers bearing his name. On foot and from a dinghy, Blake mapped the island. A recent symposium paper by Henk Brolsma that compared Blake's map with a 2002 version derived from modern survey methods and remote sensing data revealed the accuracy of Blake's work. His geological studies fared less well, but not because they were incorrect or deficient. Blake returned to an Australia involved in World War I. Soon he was in the trenches. Awarded a Military Cross, he was dead before the Armistice. His surveys, data and interpretations were published in 1943 under the name of Douglas Mawson.

At the main base, geology and cartography also overlapped. Frank Stillwell's clear maps, three now held in the National Library of Australia, delineate the rocks and contours of Cape Denison and the revelations of sledging journeys east of the Cape. Stillwell led two parties, which included Close, Laseron, and Hodgeman, who brought in consummate descriptions of coast, islets in the frozen sea, rocks, minerals and bays to 100km east of the base. Home in Australia, Stillwell's geological work was published under his own name, part of it earning him a doctorate. Later, he helped establish what became the CSIRO, though another decade passed before he gave up field work to become a laboratory-bound scientist.

Beyond the 100km boundary, the east was explored and recorded by Madigan, McLean and Correll. Madigan, also a geologist, was already distinguished, having won a Rhodes Scholarship which he deferred to go to Antarctica, and deferred again in order to lead the party that gave up another year of their young lives to search for an overdue Mawson in 1913. From the east the party brought back a chart that delineated a further 400km of coast and reports of lichens, algae and mosses. The chunks of coal they collected and photos of dolerite cliffs bore witness to climate change and active volcanoes in past eons.

As well, Madigan made a lone trek to recover a food cache which if written up in Archie McLean's overblown prose would have turned him into an instant hero.

Mawson's party of three also went east, but Mawson returned without Ninnis and Mertz and a map only of footprints. He found no geographical or geological features of note.

Likewise, the southern party of Bage, Hurley and Webb found only snow and ice. Although the South Magnetic Pole eluded them, just as it had Mawson in 1908, their magnificent 1000km sledge-hauling trek southward confirmed that Antarctica was truly a continent, not a group of large islands. Brave Bage died at Gallipoli. Photographer Hurley and magnetician Webb, who later had a distinguished academic career, must often have reflected how close they came to perishing when vital food caches were not located.

The secrets of almost 300km of land west of the base were revealed to Bickerton's team, which started out with an air-tractor, but ended up sledge-hauling through atrocious weather that remains a nightmare, as surgeon Whetter lamented. Hodgeman's charts and sketches bear witness to their fortitude. All the men of the main base party, whether mentioned here or not, suffered from episodes of snow-blindness, knew the terrible pangs of near-starvation, the agony of frozen fingers and became too well acquainted with extreme cold. Yet they continued. Shouldn't their achievements be credited to them?

Frank Wild, an exceptional leader, ensured the triumph of his eight-man party dumped on the front of a glacier. Queen Mary Land, an area even larger than that described by the main base party, was for them a winter playground, a place of great beauty, and a hostile territory to be analysed. Wild's leadership engendered no psychological tensions but only inspired them to achieve what they had committed to. Wild treated his men with kindness and consideration, and he never sulked or was disagreeable, as Charles Harrisson attests in his diary. On the Shackleton Glacier, 2400km west of the main base, no one died, although men slipped through fragile lids of crevasses into a blue deep and food ran critically short on several trips.

Despite 12 months of confinement in hut or tent and peril in the field, they still considered their final dinner together was the worst part of the whole expedition, this breaking up.

There were two geologists in this party, Arch Hoadley and Andrew Watson. They had a doctor, Evan Jones, and a magnetician-surveyor, Kennedy. Young science graduate Moyes became the meteorologist, 21-year-old Dovers was a surveyor, and at 45 the oldest member, Charles Turnbull Harrisson, was biologist and artist. With this set of skills they described the flora and fauna, the weather, the geology and magnetic phenomena, charted the topography of land and coastline, yet we never hear them mentioned.

Kennedy's exquisite hand-drawn map showing the horrifying terrain a sledging party encountered east of the hut is currently on display in the State Library of NSW Finding Antarctica exhibition. What is not shown is Kennedy's peeling face as he took sun shots and recorded co-ordinates for the making of that map. Red-haired Kennedy was, in the words of Harrisson, a colour between a well-burnt brick and a boiled lobster. Freckled, blistered, burnt, he had a bad time before taking the veil. Some of Harrisson's delicate pastel drawing are also on display. Watson's excellent photographs can be accessed on the library's website.

The thread between these widely dispersed bases was the brilliant seamanship of Captain John King Davis. With unsung crews he took the Aurora south three times: to land the parties and to relieve them. More, through dangerous ice conditions he charted unknown coastlines, made deep-sea soundings, trawled and dredged the ocean floor. Yet the charts do not bear his name and only recently have the crewmen received any recognition.

While we must honour Douglas Mawson for his dynamism in enabling the Australasian Antarctic Expedition 1911-1914, and admire his organisational achievement, we should acknowledge the men who did the work.

Heather Rossiter is a scientist and author. She has been researching the AAE diaries for the last two decades. Her latest book, Mawson's Forgotten Men: the 1911-1913 Antarctic Diary of Charles Turnbull Harrisson, was published by Murdoch Books 2011